Catch Me If You Can is a 2002 American biographical film based on the life of Frank Abagnale, who before his 19th birthday pocketed millions of dollars posing as a Pan American World Airways pilot, a Georgia doctor and a Louisiana parish prosecutor.

Played by Leonardo DiCaprio in the film, Abagnale’s primary scam was cheque fraud, which he was so adept at that the FBI eventually enlisted his help in catching other cheque forgers.

We at Sheridans rarely see such outrageous examples of frauds but in our insolvency work we regularly see examples of cons (from ponzi schemes to other, often less sophisticated, hustles and swindles).

What is a con?

A confidence trick, or scam, racket, grift, hustle, bunko (or bunco), swindle, flimflam, gaffle and bamboozle has victims, known as “marks”, “suckers” or “gulls” (i.e. gullible).

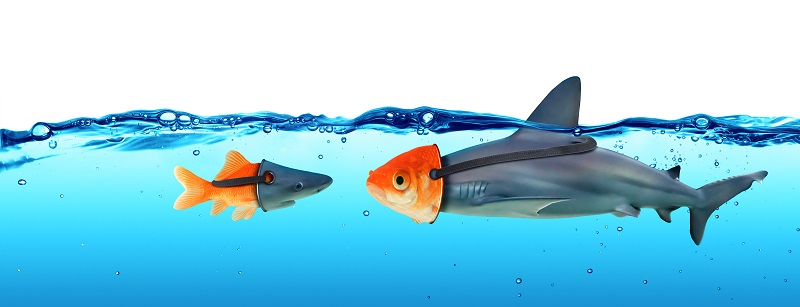

A confidence trick is an instance of deceiving or tricking someone. It is usually an attempt to defraud a person or group after first gaining their confidence.

Confidence tricks usually involve the exploitation of dishonesty, vanity, compassion, credulity, irresponsibility, naiveté and/or greed.

In addition to the juvenile Mr Abagnale, human history records an amazing number of outrageous con-artists or grifters, whose ingenuity, effort and cunning is mesmerising.

“Poyais” – A Fictional Country

The Scottish soldier, adventurer and coloniser General Gregor MacGregor was one of the most famous con-artists of all time. In 1820, MacGregor invented Poyais, a fictional Central American territory, drawing in investors and eventually colonists.

MacGregor created a guidebook detailing the geography and abundant natural resources of the country. He also went to the trouble of drafting a Poyais constitution naming himself as head of the republic (Cazique of Poyais).

MacGregor sought investors in supposed Poyaisian government bonds and land certificates and hundreds, mostly Scots, signed up to emigrate. The first wave of 250 investors sailed to the promised land of opportunity, only to find it untouched jungle, unfit for cultivation and unable to sustain even little in the way of livestock. More than half of the Poyais emigrants died in the fictitious country, primarily of disease.

Even after his trial and conviction for fraud, MacGregor continued selling non-existent land and stock to European nobility.

Painting Lies

When is a fake not a fake? John Drewe (born 1948) believed the answer is simple: a fake is not a fake if the world believes it to be genuine. Drewe collaborated with the artist John Myatt: over a period of ten years Myatt painted more than 200 fake masterpieces which were then sold by Drewe.

Drewe met the impecunious Myatt in 1985. Eventually Drewe persuaded him to paint forgeries for him. To age the freshly painted pieces, Drewe used mud and vacuum cleaner dust.

Drewe sold Myatt’s 200 or so paintings for approximately $1.8 million: he gave Myatt a total of only $100,000 while using the balance to fund his own lifestyle.

Scotland Yard called the scam “the biggest art fraud case of the 20th century”.

Drewe had to deceive the dealers and experts who inhabited London’s art world so he needed more than just convincing art work – he needed an alternative reality. He doctored the history of modern art. He would enter the archives of the Tate, and the Institute of Contemporary Arts, and insert fresh documents into existing catalogues. By doing so, he duped the experts at Sotheby’s and Christie’s, as well as a host of knowledgeable collectors.

The Devil’s Advocate

Giovanni Di Stefano, representing himself as an advocate (‘avvocato’) on his business card, was nothing of the kind.

In fact he was entirely without legal qualifications, but nevertheless was hired by such criminal clients as Dr Harold Shipman, Saddam Hussein and Slobodan Milosevic of Serbia. It is rumoured that he was also connected to Robert Mugabe, President of Zimbabwe, and to Osama bin Laden, founder of al-Qaeda. For obvious reasons he was dubbed the ‘Devil’s Advocate’.

He defrauded many other clients out of millions of dollars and between 1975 and the late 1980s served a total of eight and a half years in prison in consequence of four separate convictions in Ireland and the UK of fraud and other related crimes.

A judge called him ‘one of life’s great swindlers’. Di Stefano was more recently sentenced in March 2013 to 14 years’ imprisonment on 27 charges of ‘tricking people into thinking he was a bona fide legal professional’, which was his routine practice during the ten years between 2001 and 2011.

The Man Who Sold The Eiffel Tower

Victor Lustig was a charming, innovative polyglot, who pulled off one of the most impressive cons of all time.

After reading an article about the outrageous expense incurred by the City of Paris in maintaining the Eiffel Tower, Victor Lustig realised that a sensible solution would be to sell the Eiffel Tower.

Posing as a government official, he invited six scrap metal dealers to discuss a possible purchase of the Eiffel Tower. One of the dealers paid him an enormous amount of money in cash, which Mr Lustig packed into a suitcase and took with him to Vienna.

The buyer was too humiliated to complain to the police, and Mr Lustig got away with the scam. Even when he went back to Paris to repeat his scam and was reported to police by another scrap metal dealer to whom he tried to sell the Eiffel Tower, he managed to evade arrest.

In 1935 he was arrested and later convicted for printing counterfeit money in the United States, and died in 1947 after spending the intervening years in Alcatraz prison.

Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi (Charles Ponzi) (1882-1949)

Ponzi promised clients a 50% profit within 45 days, or 100% profit within 90 days. He used new investors’ money to repay the earlier investors. By the time of his downfall and arrest in 1920, he was making around $250,000 a day.

All fascinating but heinous con-artists. There seems to be no end to the ingenuity of the criminal. Plus there is the intriguing thought that we never get to hear about the really good cons, the ongoing, successful, undetected cons, that might be in front of our noses.