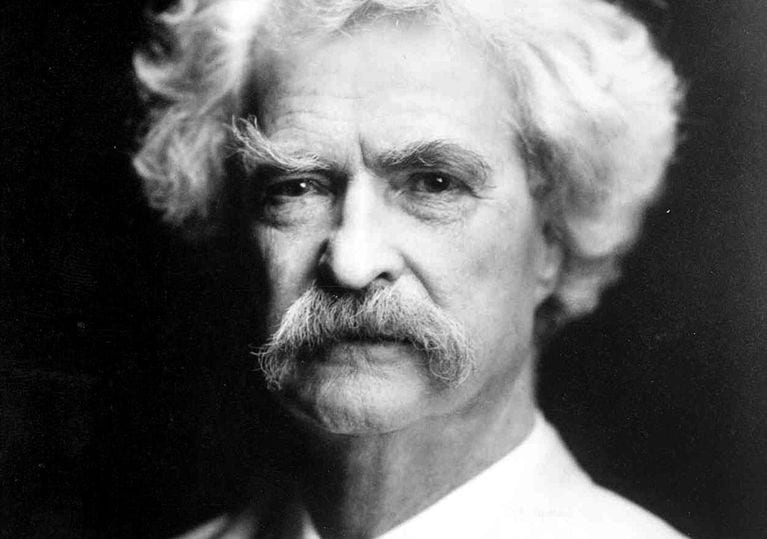

“If you tell the truth, you don’t have to remember anything.”

Mark Twain died on 21 April 1910. More than a hundred years ago. The only difference in his lifetime and ours, when contemplating lies and truth, is that today in the time it takes for the truth to put its shoes on, a lie doesn’t travel only half way around the world. Courtesy of the internet, it travels a million million times around the world, expanding and morphing as it goes, its progress unstoppably malevolent.

The controversy has raged since the evolution of ratiocination in the brain of homo sapiens about whether it is ever right to tell a lie.

Lawmakers have tried to nail down an answer, requiring witnesses in court to swear to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. Philosophers have endlessly argued for or against the case for the ‘whole truth’ or instead a ‘white lie’, dismissed in its guise as a ‘half-truth’ contemptuously by Twain as “the most cowardly of lies”.

Is it honouring someone who asks your opinion to tell them the whole truth and nothing but the truth, or is the risk of hurt feelings, misunderstanding or of giving grievous offence just too great? Should the answer to such a request be a prevarication of sorts e.g. ‘no-one cares about opinion, and this is a matter of opinion’?

Was Twain throwing up his hands at the complexity of the question when he said “never tell the truth to someone who is not worthy of it”? Of course, deciding who is or who is not worthy of it is often a moot question in itself.

But considering the conundrum can’t but be a good idea, if only that it helps keep us curious, and humble. In the works of Huckleberry Finn, channelling his creator Twain, “I was gratified to be able to answer promptly, and I did. I said I didn’t know.”